ADVENTURE

IS IN THEIR BLOOD!

(Part I, Huberht* Taylor Hudson)

“MEN WANTED: for hazardous journey, small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful, honor and recognition in case of success.”

The Times of London 1914, Ernest Shackleton’s add for his Trans-Antarctic Expedition

Today we have two very special guests from the same family; Huberht* Taylor HUDSON, who was Shackleton’s navigator, coming to our “Imaginary Zoom” through the icy pages of history and his great nephew Richard Hudson, who also sailed the Americas, Arctic and the Antarctic is joining us at “Real Zoom” from his 50 ft. schooner Issuma in Newfoundland, Canada. (*old Anglo-Saxon spelling)

Dear Huberht Taylor HUDSON, thank you so much for coming from more than 100 years ago. Can you hear us okay?

Hello! Yes I can hear you loud and clear and Oh, good to see my grand nephew Richard here!

Yes, but we would like to listen to your story first, would you please tell us about yourself

I was born on September 17th, 1886 in London as the second eldest of seven children. I joined the Merchant Navy in 1901 and was commissioned to the Royal Navy in 1913.

And a year later you saw the advertisement above and your life has changed, right?

Yes, at that time I was 28, and it sounded pretty adventurous to me. Shackleton’s goal was to cross the Antarctic continent on foot. He picked twenty-six men, including me, out of 5000 eager volunteers. 1914 I left my rank as mate in the HMS Queen Mary and signed on with this Trans-Antarctic Expedition as a navigator on board Endurance.

Is it true that the name of the ship was changed? Generally most sailors believe that it would bring bad luck.

Yes, the ship was originally named “Polaris” but was renamed as “Endurance” after Shackleton’s family motto: “By Endurance We Conquer”.

I also heard that you had a nickname as “Buddha”?

Hahaa yes, that was a joke when we were moored in South Georgia, the crew fooled me by saying that there was a “costume party” ashore and talked me into dressing as Buddha, removing most of my clothing and replacing it with a bed sheet and a tea-pot lid tied onto the top of my head with ribbons. As we rowed ashore through blowing snow, I found that I was the only one wearing any kind of fancy dress costume.

Oh dear, I hope you didn’t catch a cold! Anyway, what were the conditions when you set sail from Grytviken whaling station in South Georgia?

Actually we have been warned of ice conditions that were unusually severe that year. But the “Endurance”, our 144 ft wooden ship, was constructed to withstand the rigors of cutting through ice.

Did everything go as expected?

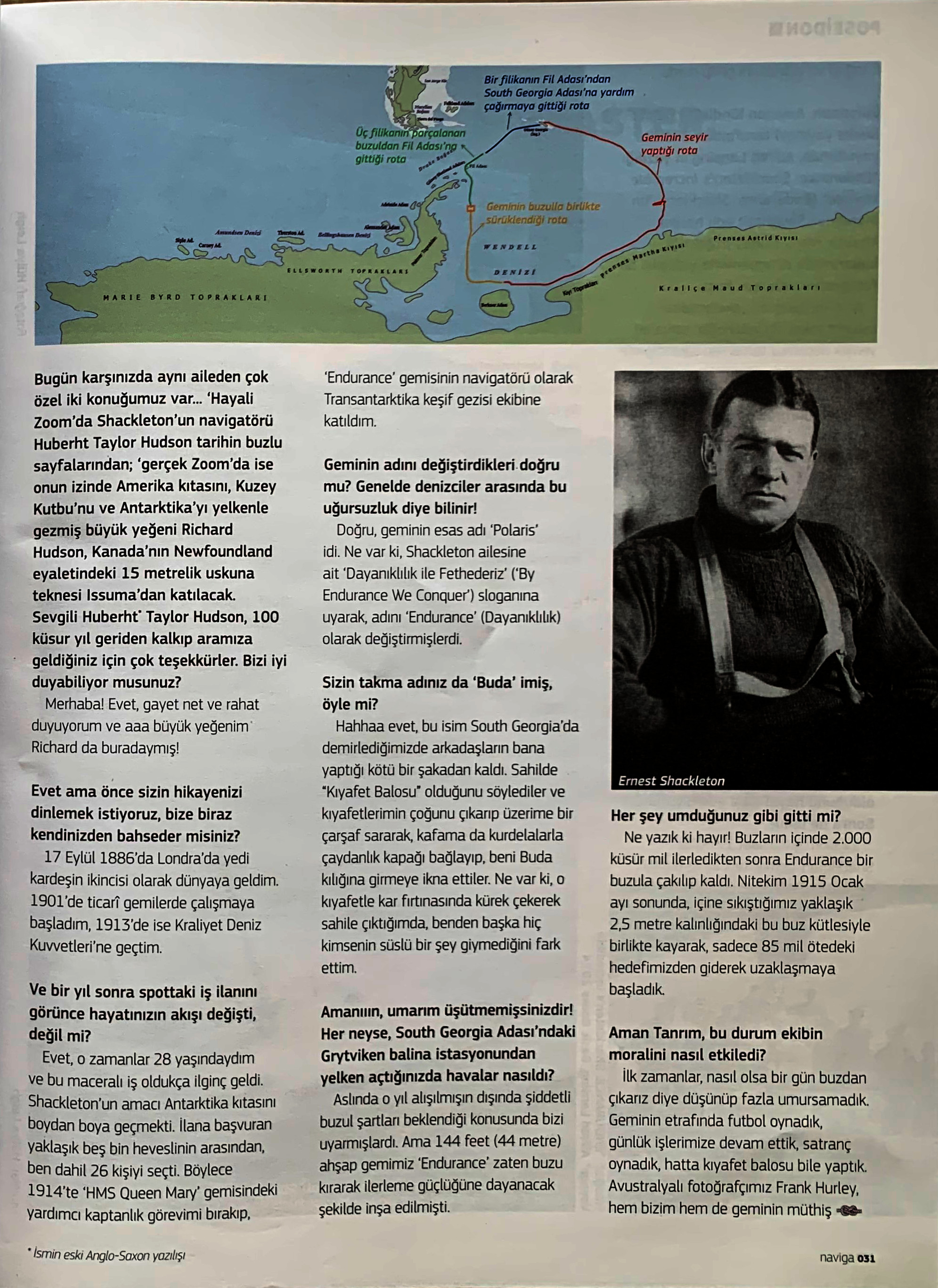

Unfortunately not! After having negotiated in the ice for more than 2000 miles, the Endurance became trapped in a floe. We were held fast in 8 ft (2,5 mt) ice on Jan 20th 1915, which started to move us away from our goal, which was only 85 miles away.

Oh my God, how did it affect the mood of the crew?

At the beginning we believed that we would get clear of it one day. We played soccer on the ice, did our usual chores on board, played chess, even had a costume ball. Our Australian photographer Frank Hurley was filming it all the time and took amazing pictures of the ship and us on ice.

I know, there is a handsome photo of you with the penguins in your arms…

Oh yes, I was famed for my ability to catch penguins, which was very much appreciated later when we were running short of food storage.

How long did the ship endure this situation?

The ship was getting pressured with huge piles of ice. We even tried to shovel them away from around the ship, but it was impossible to get her free. After 9 months, the Endurance started to heel over on her port side, the rudder sheared off, the keel was torn and the decks buckled. Shards of ice impaled the hull below the waterline and the sea started to rush in dangerously. All hands worked ceaselessly, pumping and repairing the damage, with no use at all.

I can’t even imagine how terrible it must have been. What happened next?

Oct 22nd, at 17:00 Shackleton ordered us to abandon ship. We were 1200 miles from the civilization and had no communication; there was no hope of help from the outside world. But we had full faith in “The Boss”, I mean Shackleton, that’s what we always called him.

Have you been able to carry everything you need out of the ship?

Days before she sank, we made salvage trips to the wreck periodically, until even just a few hours before we lost her, removing tons of provisions, and three lifeboats. For the next six months we camped on the unpredictable and hazardous ice flaws.

What happened to the 69 sledge dogs on board, did you save them as well?

Oh well, they were with us on the ice, but… Almost four months later by the end of Feb 1916, we were at the edge of starvation, running short of food and rationed down to one biscuit and 3 lumps of sugar a day. On March 30th Shackleton ordered us to shoot the surviving dogs. In a desperate attempt to survive, we were forced to eat them. It was a very difficult decision but unfortunately we had to do it to stay alive.

I can’t even think of how you’ve all survived after being trapped in the ice for more than a year!

At that stage we had to launch the three frail lifeboats into the most terrifying sea imaginable as the ice float started to split. I was in charge of steering the tiller of one of the lifeboats, the Stancomb Wills. After 3 days of freezing rain, frostbite and no sleep, we all arrived at the Elephant Island on Apr 23rd, 1916. Our happiness for touching solid ground after more than 16 months did not last long; as it was a godforsaken island, where no ships would pass by. Going for help was the only alternative to slow cold and starvation.

Where was the closest inhabited island to call help?

The closest whaling station was in South Georgia, 800 miles to the NE. Sailing a small open boat across the hazardous ocean was almost suicidal, but we had no choice. Shackleton took 5 more men with him on board and left 22 of us ashore.

In which group were you, on the open boat or on land?

I stayed at the Elephant Island, as I have developed bronchitis and had a festering boil on my hip, as well as frostbites in varying degrees. Our sleeping bags and clothes, which had been worn continuously for six months, were wringing wet and the physical discomforts were tending to produce acute mental depression on us.

What happened to the others on the boat?

They were fighting the largest sea swells with hurricane force winds. If the boat would have missed the tiny island, they would sail off into 4000 miles of open ocean and no one would ever know either their fate or our fate waiting on the Island.

Yes indeed! I saw the replica of that boat in Nao Victoria Museum in Punta Arenas, Chile, when I was traveling through South America in 2018. I could not believe how they survived in that boat in the ocean...

We added 2000 pounds of rocks and gravel for ballast, added a canvas deck to make the lifeboat “James Caird” slightly more seaworthy. But they had a real tough time to break the 15” (38cm) of ice building at night on the canvas deck; otherwise its weight could sink the boat.

It is a miracle that they crossed the Southern Ocean in a small boat during the harsh Antarctic winter and landed safely to the south coast of the island

Absolutely, later they told us that the main pin holding the rudder fell out just as they landed. So they had no chance to sail around the island to the Norwegian whaling station. Shackleton and two of his men crossed the treacherous glaciers and crevasses on foot for 36 hours and reached the base. It was a superhuman feat. It took him three attempts to come and rescue us, but he saved us all safely! At the end, upon our arrival back to England, we all received the honor and recognition he has promised in his earlier newspaper posting.

On the other hand, only a few days after you sailed south to the Antarctic, World War I started, and if you had stayed with the Navy, maybe you would have less chance to stay alive during the war.

That’s very true…

Thank you so much for sharing your memories with us in our “Imaginary Zoom” meeting. Now we have your great nephew Richard HUDSON with us from Canada, who is also following your footsteps, having sailed the Americas, Arctic and the Antarctic. He even stopped by the Elephant Island!

Aha, he must have my genes. If you will excuse me for now, I will turn off my microphone, as I am feeling a little tired. But I will be happy to listen to Richard’s story.

Well of course, please have some rest. And oh, we are also running out of time right now, how the time flies! So we will listen to your great nephew Richard Hudson’s adventures next month in our “Real Zoom” meeting at Naviga April 2022 issue. Looking forward to his story…

------------------------------------------------

Timeline for Endurance Expedition:

August 1914 Endurance leaving UK

December 1915 Endurance departs South Georgia

Febuary 1915 Ship is thoroughly ice locked

October 1915 Vessel’s timbers start breaking

November 1915 Endurance disappears under the ice

April 1916 Escaping crew reaches Elephant Island

May 1916 Shackleton goes to South Georgia for help

August 1916 A relief ship arrives at Elephant Island

ADVENTURE IS IN THEIR BLOOD!

(Part II, Richard Hudson)

“MEN WANTED: for hazardous journey, small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful, honor and recognition in case of success.”

The Times of London 1914, Ernest Shackleton’s add for his Trans-Antarctic Expedition

You may recall this job posting in 1914 for Sir Ernest Shackleton’s the Trans-Antarctic expedition, the most famous survival story in naval history, from last month's 'Naviga February 2022' issue. Huberht* Taylor Hudson, (*the old Anglo-Saxon spelling of the name) chosen by Shackleton as the Navigator among 5000 people, came from the icy pages of history to share his wonderful memories with us at our “Imaginary Zoom” meeting.

His great-nephew, Richard Hudson, who has sailed the Americas, the Arctic and Antarctica in his footsteps, will join us today on board his 50 ft schooner Issuma in Newfoundland, Canada. His adventurous story is just as captivating as his great-uncle's!

Dear Richard Hudson, we ran out of time last month talking with your great uncle, but we've been looking forward to hearing about your adventures. Thank you very much for attending our “Real Zoom” meeting, despite the time difference. For me it was an incredible coincidence to come across your website https://www.issuma.com and your YouTube channel https://www.youtube.com/SchoonerIssuma while researching your great uncle's story.

Did receiving an interview request from Turkey surprise you?

Yes, I was surprised!

Your great uncle Huberht was born in UK. Were you also born in UK or in Canada?

My grandparents (Huberht’s brother) moved from England to central Canada, to farm. Nothing to do with the sea, oddly enough—I assume that was just for economic reasons, but I never asked them why. Both my parents were born in Saskatchewan, Canada. And I was born in Toronto, Canada.

Did you grow up listening to the interesting stories about your great uncle?

Yes, I learned of my great uncle at a young age. My father talked of him, though they’d never met.

When did you start to dream about sailing, traveling?

As a child, I had severe asthma, was often in hospital, and was mostly confined indoors. I had a light on the ceiling of my bedroom with a map of the world on it. I would look up at that light and dream.

I read stories of travel and adventure, and I dreamed of going to the far-off, wild corners of the world, especially the far north and south. But I didn't travel, I didn't go on adventures. When I was a teenager, asthma medicines greatly improved, I was suddenly able to live a normal life. I was determined to live an interesting life, full of travel and adventure. I've been living my dreams--or working towards them--ever since.

What was your first sailing experience?

As a child, I was fascinated by canoes, and while I’d never been in one, I was determined to get one. I saved all my money from delivering newspapers until I had enough to afford a canoe. I was 12 or 13 when I told my parents I was going to buy a canoe and learn to paddle it. They had grown up on farms in the middle of Canada, and weren’t water people. They said no, but put me in some free sailing lessons that were being offered for kids.

So I took sailing lessons in old, 8m long, double-ended, riveted steel ships liferafts, rigged as dipping-lug schooners, with leeboards. Great boats for teaching a bunch of energetic youngsters to sail in—on each tack one needed to pull the yard back and around the mast, as someone else released the sheet and someone else hauled in the other sheet. That got me hooked on sailing, and I focused on that.

It is fascinating that you learned to sail in a ship’s liferaft, where your great uncle saved his life in a liferaft, as if you were starting from where he left off. What happened next?

I got on a brigantine-rigged training ship for teenagers, and spent three years sailing all summer, working on the ships and studying seamanship & navigation on weekends in the off-season. At 17, I had worked my way up to Watch Officer when I left Toronto to try riding my bicycle to Alaska (I ran out of money after 2,000 km and started working instead).

Did you ever work in an office, for how long? When and what made you to quit your job and move to live on a boat?

I worked in the computer industry, 12 years of that for large banks in New York. That was a world of working in high-rise office towers looking out over the waters of the harbor.

I went to work with a goal of making enough money to afford to buy and sail an ocean-going boat, and I kept myself focused on that goal, putting in long hours towards it. Every day as I went to work, every time I looked out at the harbor, I told myself I was getting closer to sailing the world.

At first, I spent my free time wandering the docks, dreaming of the sea. Then I joined a sailing club and crewed on racing boats whenever I could. Later, I bought my first cruising boat, a 12m gaff-rigged steel schooner, Orbit II. That boat required much work, but I loved sailing it on evenings and weekends, and later it took me across the Atlantic Ocean.

When I had my boat ready and enough money saved, I quit my job, moved out of my apartment and started sailing full-time. That was in 2000.

Three times I found another job and went back to work after going off sailing for multiple years. At first, I enjoyed both the sailing life and going back to work later. As time went on, I enjoyed the sailing life more, and the working life less. I’m sure a lot of your readers will understand that :)

When did you start to live on your recent boat, Issuma?

Issuma is my fifth sailboat, and my third offshore-cruising type of sailboat. After Orbit II, I bought another schooner, Rosemary Ruth, in 2004. And I have mostly been living and sailing on board Issuma since 2008

What does Issuma mean?

Issuma is the Inuktitut (Eskimo) word for ‘knowledge, idea, wisdom or mind’.

What are the technical specialities of Issuma?

Issuma is a Damien II steel boat (50 ft / 15 mt) build in France, rigged as a staysail schooner, with all the ballast in the centerboard / lifting keel. It was designed for sailing to and cruising in Antarctica, so extremely tough and seaworthy, and able to carry a lot of supplies.

The hull shape is designed to be forced upwards by ice pressure, rather than being crushed. Raising the centerboard gives less for the ice to “grab” if trapped in ice, and allows motoring into shallow areas (1.3m draft with the centerboard up). When the centerboard is down and locked in the sailing position, draft is 3.2m, so the ballast is low.

You’ve sailed around the Americas between 2008 - 2016 and in 2011 you’ve accomplished the Northwest Passage. What was the most challenging part of it for you?

The most challenging part was after the NW Passage was technically completed, being weather-bound for a month in Yakutat, at the north end of the Gulf of Alaska in October.

The winter weather patterns appeared to come early that year, and three times we left, only to turn back. We were getting about 48 hours between Force 10 storms, and that just wasn’t long enough to feel comfortable about getting to an unfamiliar port with long hours of darkness and anchored or docked well enough for a storm. After a month, we got three days of winds below gale force and we made it to the Inside Passage, from where hops could be much shorter, as there were many islands to take shelter from storms at.

Have you ever had any kind of survival experience?

My gaff-rigged schooner, the 12m Orbit II rolled over in a Force 9 (strong gale) and later sank 300 miles south of Iceland, while en route to the Canaries.

We had been hove-to, which is what I normally did in gales back then (this happened in 2002), and both of us were below when we were suddenly knocked down 80 degrees. This had never happened to me in other gales, and I went towards the deck to see what was happening. My foot was on the bottom rung of the ladder to go on deck when suddenly I was thrown around the cabin, things were thrown at me, my head was briefly underwater, and within less than five seconds, the hatch I had been about to go through was just a hole in the cabintop.

The masts and booms and gaffs—all wood—had broken off and were floating in the water, still attached by the rigging wires, and we were downwind of them. The seas were the height of two-story houses (7-8m), and the top metre of the waves was breaking. The waves broke on the masts, booms & gaffs, then came to the boat and broke ahead and astern of us. That saved us from rolling over again and taking on water through the holes where the hatches used to be.

We worked to try to cover over the holes where the hatches used to be. My crew was injured in the rollover, and, to make a long story short, after 18 hours, we were lifted off by helicopter and the boat sank. The full story is at https://www.issuma.com/rhudson/orbitlog/OrbitsLastVoyage.htm

Did you generally sail single-handed or took crew with you? Which one would you prefer?

Sometimes I sail single-handed, sometimes I take crew. I enjoy both of those experiences—they’re quite different. Sailing with others allows you to share the experience with other people, which is wonderful. Sailing alone can be more work, and it certainly teaches you to become efficient at tasks, but it’s a more intense, harmonious experience.

What was the longest time you’ve sailed alone at sea?

Almost two months, from the island of St Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean to Virginia, USA. It was a great experience, far more enjoyable and rewarding than I had expected. The warm weather and no gales certainly helped make it pleasant, but it was the deep sense of satisfaction I got from feeling more in tune with the environment around me.

Did you sail to Elephant Island in Antarctica? How did you feel? It must be emotional to know that your great uncle was there suffering but survived.

Yes, I sailed there in January, 2016. I sat out a storm at anchor off Elephant Island. I was glad to have a much better boat to do it in than the small boats they landed with!

Where I anchored wasn’t near where my great uncle spent those months, because where they chose to land was not a sheltered place. Where they landed was where it was most likely that ice conditions would permit a rescue ship to approach, not a sheltered place with much protection from storms.

When I was considering where to anchor, I thought about how greatly easier my trip was than my great uncle’s, being able to choose a place with protection from storms (not to mention having a much more seaworthy boat than the lifeboats which they had).

Did you ever think of writing a book?

Yes, but I’m a slow writer, so it hasn’t happened, yet :)

Did you ever sail the Mediterranean, the Turkish coast?

Not yet! I’ve heard great things about the Mediterranean and especially the Turkish coast and I’d love to sail there one day.

What are your future plans?

I’ve been planning to charter my boat to Greenland (https://www.issuma.com/adventure) and around the North Atlantic for two years, but I have been delayed by lockdowns. Perhaps I will be able to start that this summer, perhaps not—it’s difficult to plan to go long distances now.

In a more general sense, I plan to keep sailing :)

If anybody wants to join your adventurous charter trips in future, how can they contact you? Do they need to be experienced sailors?

No, they need to be passionate about going on an adventure. Previous sailing experience helps, but is not required. I can be contacted at adventure@issuma.com

Thank you for sharing your inspiring story with us. We do hope to see you and Issuma in Turkish waters one day.

I look forward to sailing to Turkey!